On cross-country road trips such as the one I took this summer with Mugsy, my English Bulldog, America’s energy generation is nearly always in view from windmills to oil wells to refineries to coal-fired and nuclear plants to fracking.

What wasn’t apparent on the drive is that according to this chart created to illustrate the annual analysis by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, of the 95.1 quadrillion BTU’s of the energy input into the U.S. economy last year, 61% were wasted, including 36% sourced from petroleum alone.

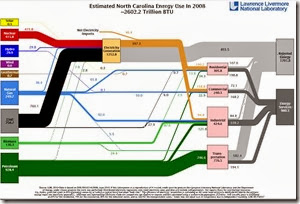

Illustrations of input/waste for each state are also provided.

As an example, North Carolina, where I live, is shown in this blog. Apparently, we waste more than 65%.

Click here for the energy input/waste for other states. My native Idaho wastes less than 54% The proposed bipartisan Shaheen-Portman legislation is supposed to make us more efficient, while taking the equivalent of 22 million cars off the road.

Barry Fischer with the energy analytics start-up, Opower, notes on its Outlier blog that we would have to go back to 1970 to find a time when the U.S. actually used more energy input than it wasted. Productivity in 2012 was the worst in a decade.

When I returned from my trip, I happened to read an article entitled “Turning Grass Into Gas” by Bruce Barcott. It is a very thorough and even-handed overview of what shows in the input/waste chart as biomass.

This isn’t corn ethanol. It involves cellulosic conversions of waste byproducts such as sugar cane refuse, corn stover (leaves and stalks,) Switchgrass, municipal yard waste, and even garbage into the stuff used to fuel Henry Ford’s first vehicles. It had been invented in the 1820s.

Before full-cost accounting began to reveal petroleum’s hidden costs, it put grass gas out of business. But now some major players such as DuPont are involved and some big, commercial-scale refineries are shipping product.

I don’t believe I had ever laid eyes on Switchgrass until my trip out west. Growing up to six feet tall, this native American perennial grass had covered much of the country east of the Rockies until I passed through an area just west of Knoxville, Tennessee.

Just past Knoxville, running south along the Tennessee River, there are now 63 farmers raising more than 5,000 acres of Switchgrass to supply a biorefinery co-owned by DuPont.

I happened to drive past another DuPont commercial-scale biorefinery near Nevada, Iowa on the return leg of my trip. North of Des Moines, it will be the largest in the world, producing cellulosic ethanol from the residues of corn grown in a 30-mile radius by 500 farmers.

It will take 375,000 tons of waste from corn fields and convert it into 30 million gallons of ethanol a year.

North Carolina State University has modeled growing areas for Switchgrass in the counties south and west of Durham, where I live. It thrives on soils that have been depleted by crops such as tobacco and cotton.

Growing and turning this grass into gas would be a far less wasteful approach than “fracking” proposed near there.

Switchgrass delivers an average of 13 units of energy for every one consumed in fertilizer or fuel. It also works great against erosion, rehabilitate depleted soils and provides a good habitat for wildlife.

If reading OnEarth gives you heartburn, try the write up on the same cellulosic potential this month in Forbes, written by Houston-based Christopher Helman.

My bet is that the 4.32 quadrillion BTU’s injected into the economy is about to get a lot bigger.

No comments:

Post a Comment