I’ve always been interested in the evolutionary history of community destination marketing organizations (DMOs,) my now concluded career.

Not just when they began nearly 120 years ago or the Progressive Era that spawned them, but how they and the communities they serve evolved over time.

Keep in mind that my career not only spanned more than a third of that history but due to influential mentors such as Charlie Gillette, and Bob Sullivan and those who mentored them, my career span covers influences from all but 15 to 20 years since the first DMO was formed.

The career DNA passed to me from them and from their mentors to them stretches back to the period of 1910-1915 when less than 20 DMOs were in existence. This was in the years before a DMO trade association was formed.

This was back when asphalt had just been invented and pavement applied to only 144 miles of roadway. It was also the period when passenger air travel first evolved, although only over waterways using airboats and a full decade before mass tourism evolved.

It was also the period when passenger air travel first evolved, although only over waterways using airboats and a full decade before mass tourism evolved.

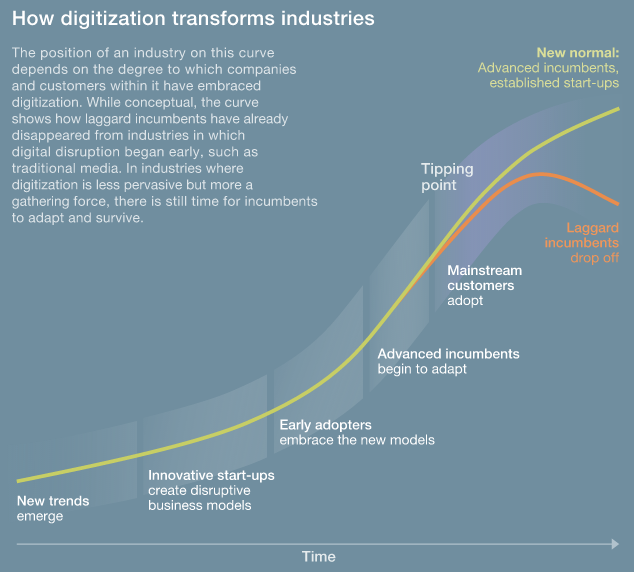

Those mentors came to mind this month while reading a new McKinsey report on the state of how digitization transforms industries written by directors Martin Hirt and Paul Wilmot.

Equally applicable to the evolution of marketing is their excellent typology shown as an image in this blog.

My two mentors in 1974 came from very different backgrounds: one in publicity and the other in sales; but they were both DMO innovators who could quickly read trends and translate them into both strategy and execution far in advance of their peers.

That was the year my mentors persisted until the trade group for DMOs finally added the word “visitor” to its name, four decades after leisure tourism by auto had skyrocketed.

Unfortunately, trade associations are usually dominated by mainstreamers, or at best late adopters, who are forced to tolerate the occasional innovator. This is illustrated by taking four decades from the emergence of tourism to recognize that it included much more than conventions.

The association will celebrate its 100th anniversary this summer in Las Vegas, Nevada. That may seem an odd and extremely unseasonable choice since the first DMO was founded in Detroit and the association was founded in St. Louis.

I’m not sure those cities are any less unseasonable in the dead of summer and probably even more humid, although as a westerner I know that “dry heat” is a myth.

Las Vegas was an innovator when its first marketing effort formed after World War II as a news bureau. After a time it fell under the chamber of commerce but was independent by the early 1970s when I joined the profession.

Most DMOs started as sales organizations so this was not only novel but incredibly farsighted. Las Vegas grasped that community marketing is first about fostering image and that PR and publicity are many times more powerful overall than advertising.

Any number of books document that it is the news bureau—not Bugsy Siegel or mobsters or their successors—that made the destination what it is today. When I started in destination marketing circles, the news bureau’s head, Don Payne, was the face of Las Vegas.

Las Vegas didn’t get everything right. Nevada pioneered the room occupancy tax in 1955 but dedicated it only to a recreation authority to fund the building of a convention center.

Slowly it was realized that it is marketing, not facilities, that drives visitation, and that overall destination balance trumps volume in any one area of activity.

By the mid-1970s, just before I became a CEO, the organization morphed into the Las Vegas Convention & Visitors Authority to do community destination marketing. The News Bureau moved under the LVCVA in the early 1990s.

The organization remains highly innovative, sharing the number one spot in the world for best practices with the DMO in Durham, North Carolina where I live.

Durham and Las Vegas have historically taken two different paths as destinations. They were settled about the same time. Although Durham was quicker to be incorporated as a city, their respective counties were formed only about two decades apart.

The two cities were about the same size when I visited Las Vegas for the first time in the mid-1960s. But Durham was about 10 times larger when the two took very different approaches to sense of place in 1920.

At the time, Durham’s founding generation took the route of preservation of place-based assets, e.g. historic buildings, indigenous cultural events, nature and nationally known but homegrown chefs and sense of place.

Las Vegas, when it felt the first stirrings of tourism a few years later in the 1930s, took the direction of gaming casinos and a simulated sense of place.

There are still remnants of the real Las Vegas but the glare of the strip clouds its view. While both at one time were known for “sin,” one tobacco, the other gambling, Durham took a different route to sense of place.

Durham was more than two decades slower to launch visitor-centric economic and culture development but when it did, its vaunted sense of place was well evolved and took center stage in community marketing.

Each community is the center of its own MSA but while the greater regions are similar in size now, Durham’s is polycentric, a geography that has also helped it retain its unique cultural identity as well as the feel of a much more intimate, manageable and inviting place.

In the early 1800s, the meadows for which Las Vegas is named became a stop for traders on the Old Spanish Trail. In 1855, Mormons created the first real settlement and a historic fort, a site that you can still visit today.

In the 1930s, Hoover Dam was created impounding Lake Meade, the largest reservoir in the U.S., 35 miles outside Vegas. At a time when the first generation in Las Vegas settlement was busy surrendering its sense of place, the first generation in Durham’s settlement was already busy preserving and restoring its genuine sense of place.

I went on a trip down to Las Vegas in 1966 with my maternal grandfather as a high school graduation present. My grandmother had just died after a decade-long illness. He knew I like Johnny Mathis from the albums I had listened to when we visited.

So we tooled down in a my uncle’s ‘65 Mustang convertible (he was serving what would be three tours as a fighter pilot in Viet Nam) to see Johnny sing in the newly opened Caesar’s Palace.

Las Vegas was still people-scaled back then and downtown Las Vegas was symbolized by The Mint, where country-legend Patsy Cline had performed a year before her she and three others including two other country stars died in a small plane crash.

The last song she sang live was I’ll Sail My Ship Alone.

My first trip was sandwiched between the Beatles two years earlier and the arrival of Howard Hughes four months later. We took in other attractions too, but the opening of Caesar's during my right of passage marked the end of an era and the beginning of mega-themed-casino hotels.

It was a lot for an Idaho boy to absorb, but even then I could sense that the community’s personality was being overwritten.

By the time I arrived in Durham in 1989 for my fifth DMO startup, The Mint was gone. Ironically, I had been succeeded in Anchorage by Bill Elander, a friend, former MGM executive and Thunderbirds pilot on whom Las Vegas had worn thin.

Near the end of my career I was on the DMO trade association’s International board of directors and attended a board meeting held in Vegas. We were treated to a light show in a fountain but not to the genuine Las Vegas.

I’m definitely not LV’s target market. Only the Ferrari dealership/museum offered any appeal, but even that didn’t seem real somehow.

The only highlight for me of that final visit was a quick run up into the El Dorado mountains in back of Vegas to see Hoover Dam along the Arizona border. Coming back down, in the far distance you can still catch a bird’s eye view of the real Las Vegas from there.

Places such as Las Vegas today are where you go to see simulations of other places but little of it is genuine or authentic anymore, which is a much more popular reason people travel.

Few visitors see the the real Las Vegas—or even care—but at least that community committed fully to simulation rather than seeking to emulate others that have slowly surrendered any distinct sense of place, becoming little more than Anywhere, USAs.

You can’t have it both ways. Durham and Las Vegas each made a better choice.

When DMOs convene in Las Vegas this July to toast the century since their trade association’s founding, I doubt more than a few will care to understand these distinctions.

Those that do I bet are DMO innovators.

DMOs are at a crossroads. Sense of place in many communities is disappearing and often rather than fulfill their role as guardians of sense of place, many DMO’s serve as complicit enablers, especially those addicted to facilities.

Many, I fear, will fail to grasp that differentiation and fostering sense of place is what destination marketing is all about. Others labor in communities with deaf ears.

It is fitting they meet in Las Vegas where the contrast is so evident.

No comments:

Post a Comment