From a vista in the center of San Francisco known as Twin Peaks, you can look down on a spot in the Mission District with the Bay glimmering to the east.

For a few years in the early 1860s this was known as Camp Alert, a race track-turned-Union Cavalry training facility.

I’ve always wondered how Thomas K. Messersmith, one of my maternal great-great grandfathers, who was a fourth-generation Southerner and native Missourian came to enlist to fight for the Union and train there, so far from home.

Tracing genealogy is a journey, often beginning by tracking down documentation for family legends. But even when found, each revelation usually still leaves a loose end or two, that once tied open yet another revelation.

By the 1860 census, my great-great grandfather, a few weeks shy of 26 years old, was bunking with two other miners who were well into their 30s, T.H. Wilson from Virginia and N.F. Scott from Maryland.

They were living in a boarding house in Virginia City, Nevada which was then a part of Utah Territory and the site of the Comstock silver discovery only a few months earlier.

I doubt he came out to the California Gold Rush a decade earlier because the census then shows him still at home in Missouri.

But Virginia City had not only been named by Southerners, it was a hotbed at the time for secessionists who were gloating at having defeated a proposal for statehood because it included a prohibition of slavery.

My great-great grandfather had somehow formed a friendship with Samuel Clemens, who was a year younger and yet to adopt his famous pen name “Mark Twain,”

Because they were born and raised in very different parts of Missouri, I suspect they had formed a bond once Twain arrived in Virginia City with his brother, probably as much over as shared prowess for playing cards as briefly sharing a mining claim.

These fragments can be pieced together from references in collections of Twain’s letters from that time, which also confirm that my great-great grandfather would often be referred to be “Smith,” a truncation of his last name, Messersmith, just as my great-grandfather Ralph would later do.

This discredits another family legend that the truncation was the result of discrimination during World War I.

My great-great grandfather gave up on mining around the time he crossed paths with Twain or shortly thereafter and headed up and over the Sierra Nevada’s and down to Stockton to enlist for the Union on October 3, 1861.

Interestingly, Twain had already served a two week stint with a Confederate militia back in Missouri and still had Southern sympathies at the time.

This and the dissention back in their home state must have led to some interesting conversations between the two Missourians.

The California into which my great-great grandfather rode had been in deep turmoil since a deep spit the year before in the Democratic Party, which had resulted in the election of President Abraham Lincoln with just a third of the vote.

Rampant secessionist conspiracies had compromised local militias and more than a few law enforcement official, especially in Southern California, leading to public demonstrations by both sides.

At the same time, regular Union Army units were being withdrawn to the east and several new Union regiments of California Volunteers were being enlisted to protect communications and critical ore shipments needed to fund the war effort from sabotage and attack.

My great-great grandfather made a conscious decision which to my prior understanding was contrary to his both native state and his friends.

But digging further I have learned that it was me that was very much misinformed.

It took me a while to track down that he initially enlisted in Company A of the Third Regiment which was an Infantry unit, but that didn’t jive with family legend that he was Cavalry.

Nor did the date of that unit’s arrival in Salt Lake and its various assignments align with the date and place he eventually mustered out of the army at the end of his tour.

Finally, I found a small reference in one military citation that read, “see Company L Second Regiment Cavalry.”

After being outfitted at the Benicia Arsenal, he may or may not have participated with Company A in the Bald Hills uprising that ended at Fort Baker before being transferring to Cavalry.

It is more probable that he was moved to Cavalry training in San Francisco almost immediately.

A hint is provided in one of Twain’s letters, dated May 17, 1862, where he asks another friend to send a pair of Spanish spurs hanging back in his office out to my great-great grandfather.

Between late that summer and early fall, with Cavalry training at Camp Alert behind him, at least a part of my great-great grandfather’s company in detachment with another had joined Col. Patrick Conner in Stockton.

From there, along with 1,000 other Cavalry and Infantry, they moved in phases over the Sierra Nevada’s and out into the Great Basin along the Overland Trail.

They rode first to Fort Churchill about 30 miles east of Virginia City and then proceeded on to secure Fort Ruby, near, coincidentally, where two other of my great-grandparents would drive stagecoach a few decades later.

Eventually, they based at Camp Douglas (later re-named Fort Douglas,) a newly created installation on a bench of the Wasatch Mountains above Salt Lake City, where, again coincidentally, my father would be inducted into the army during WWII.

From there, my great-great grandfather’s Cavalry company would deploy to protect wagon routes in mountain valleys to the west where they were under constant attack.

This was all during the period when the Pony Express was phasing out and the first Transcontinental Telegraph was being completed along a major freighting corridor to the east carrying bullion and supplies for the war effort.

It is hard to relate just how broadly and intensely these facilities were under attack during the Civil War from warring bands of Paiutes and Shoshone-Bannock peoples, stretching in a “T” up the Upper Snake River Valley to what would become my birthplace eight decades later.

So I will insert this link as background.

Because so much of the family legend surrounding my great-great grandfather’s Union Cavalry experience has now been documented, I have no doubt that one day I will find verification of another part.

As the story has been passed down, the scar through his trademark mustache was the result of deflecting a Shoshone arrow that would have struck Colonel Connor.

My initial skepticism, at least of this particular hand-me-down family legend, has repeatedly proven groundless so far.

When digging into family history it helps to remember that legends are traditional stories regarded as historical but unauthenticated, usually because those details have been lost as the stories were passed down.

My great-great grandfather was notoriously quiet and solitary, spending weeks at a time herding sheep up into several of valleys along the Oquirrh Mountains where he had once patrolled near the end of his stint as a Cavalry trooper, including Rush Valley where attacks were especially frequent.

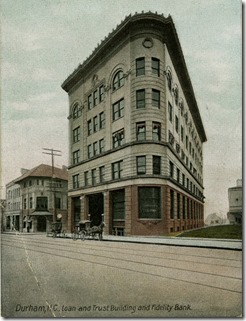

(Another, Cedar Valley, where he settled, is shown above.)

He became a Mormon and spent the remainder of his days alongside the very Overland Trail he had help protect as a means to hold the Union together never revealing what I now know of how he came to choose that side.

But in researching this blog, I think that has become clear.

Missouri, it turns out, may have had a very vocal population who had migrated from slaveholding states but by the time of the Civil War, while a neutral border state, it was firmly Unionist in sentiment.

It had its share of secessionist scheming.

But given the opportunity to vote for secessionist candidates to a convention, it overwhelmingly instead voted for Unionist representatives who voted 99-1 against secession and 70-23 against solidarity with Southern slave states.

Most telling about my great-great grandfather’s decision is that those fellow Missourians who enlisted to fight for the Union outnumbered those who enlisted to fight for the Confederacy by nearly 4-1 (110,000 to 30,000.)

Mystery solved at least for my great-great grandfather.

Unfortunately, far too many Americans are still fighting that war.